Conceptual basis

Context

Social development is now a central factor of economic development. African leaders have clearly expressed their political intent for a more inclusive and transformative growth path. The global and regional development frameworks, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Africa’s Agenda 2063, provide the anchor for equality, sustainability and growth to leave no one behind.

Embracing inclusiveness is not a new idea. World leaders at the 1995 World Summit on Social Development in Copenhagen acknowledged the importance of social inclusion and integration to achieving sustainable development worldwide. For the first time, a simple model of deprivation was shifted to a holistic one of human poverty, exclusion, and participation.

Global leaders at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012 restated their commitment to promoting social integration through creation of more cohesive and inclusive societies. Exclusion as a development barrier started to get more attention.

Regional commitments to inclusive development

The importance of inclusiveness has also gained prominence in the continent’s development agenda. African leaders have committed to the 1995 Copenhagen Declaration and Programme of Action and the 2008 Windhoek Declaration on Social Development and Social Policy Framework for Africa. Both declarations are instrumental in advancing Africa’s social development priorities. Governments are also addressing the specific challenges of vulnerable groups – including young people, women and the elderly – through the International Conference on Population and Development, the Beijing Platform for Action, the Ouagadougou Plan of Action, the Abuja Declaration, and the Madrid Plan of Action on Ageing.

But the desired outcomes have not yet been achieved. Until recently, the challenge of exclusion and how to address it in national development planning was little understood. Apart from constraints of data, institutional capacities remain weak. Monitoring mechanisms to assess inclusion in Africa are also lacking, leading to inadequate statistical follow-up and policy formulation.

To accelerate progress on reducing exclusion, governments need policies that make equality and inclusion a choice rather than a by-product of development strategies. An inclusive structural transformation requires strong and responsive developmental states and long-term development planning that is consistent with the principles of African Agenda 2063 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

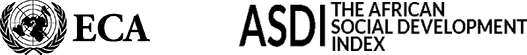

A new paradigm for inclusive development

To respond to these challenges, ECA has been at the forefront of proposing an economic and social transformation agenda for Africa. In terms of economic transformation, Africa needs to build on its comparative advantage and focus on industrializing its agricultural and commodity sectors, improving regional integration and adding value to its products, in order to increase its competitiveness and productivity. With regard to social transformation, the continent needs to ensure that economic development is sufficiently inclusive and that it translates into improved wellbeing of Africa’s populations. One of the key components of social transformation is the need to address the excluded groups, essential for ensuring a balanced and equitable development. This would provide the basis for redressing specific exclusion patterns, through effective policy formulation at the national and subnational levels.

Defining human exclusion

Exclusion is multidimensional and difficult to define unless a clear framework is established on how and what aspects of exclusion are to be assessed. There is clear recognition, however, that an ‘excluded’ society is likely to impair development, slow down economic growth, and trigger social and political instability. This is indeed what the continent is currently experiencing, with sustained economic growth unable to ensure the inclusive and equitable distribution of its benefits across populations. Moreover, evidence shows that the pace of progress towards inclusive development in Africa is too slow and its drivers too limited to meet the needs of its poorest populations. It is therefore critical to ensure that these groups are integrated into development and decision-making process, so as to accelerate the transition towards a more sustainable and equitable growth.

In this context, human exclusion and the commonly-used term of social exclusion take different meanings. Social exclusion generally refers to a person’s or a group’s inability to participate in social, economic, political, and cultural life and their relationships with others. Human exclusion can be defined as an individual’s inability to participate in and benefit from the development process itself. Human inclusion may therefore be seen as a stage prior to social inclusion: people need to be part of the development process, and benefit from it, before they can participate.

Key drivers of human exclusion

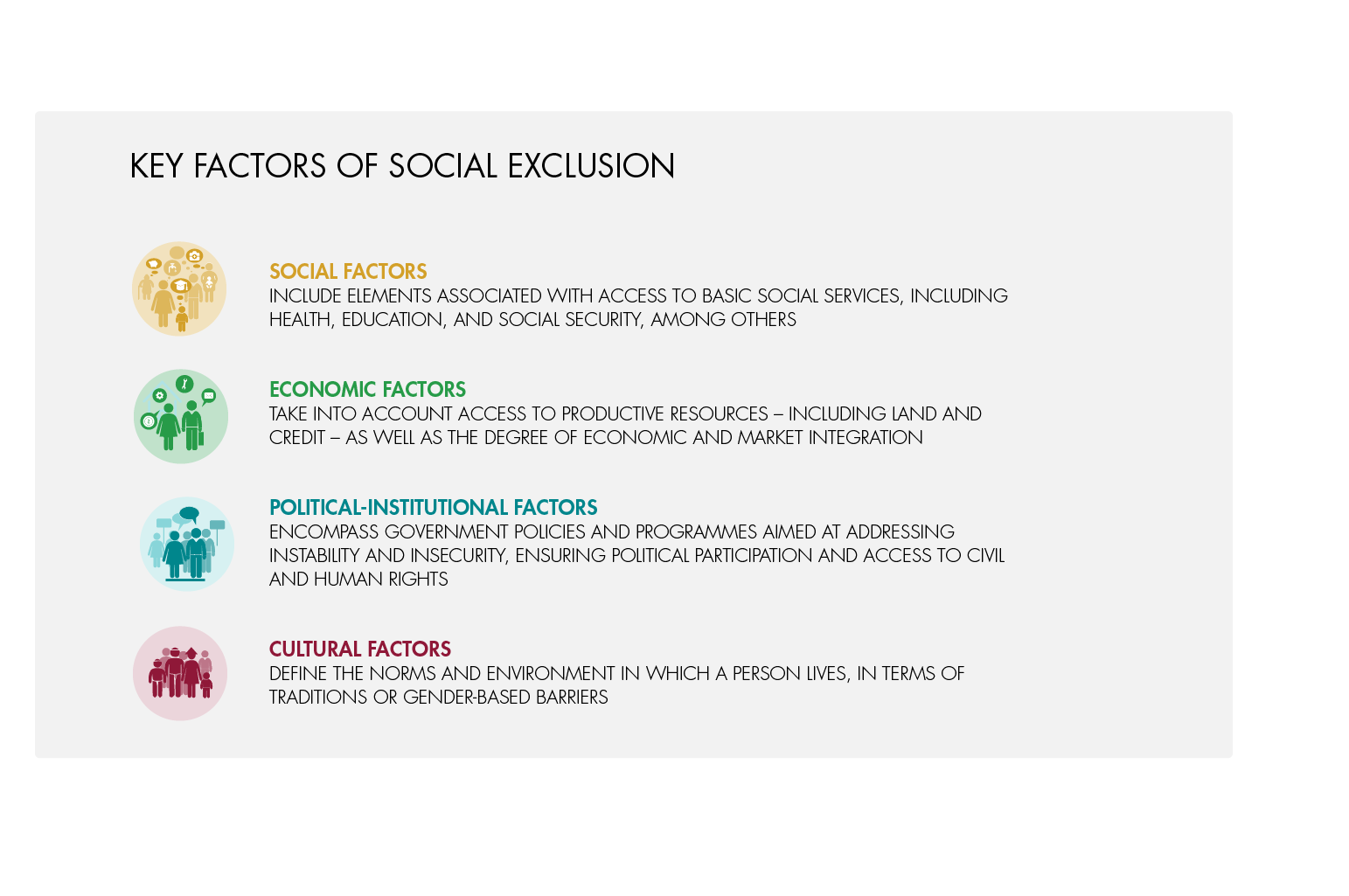

Exclusion is structural and needs to be prioritized to sustain growth and maintain peace. Exclusion also skews development dynamics, economic opportunities, and job creation – leaving the economy with a narrow base and greater vulnerability to external shocks. In addition, exclusion — whether based on income, gender, location, or political factors — has clear social costs. It is argued that exclusion is often driven by the interaction of a series of contextual factors.

These factors are often a consequence of policies and programmes and can affect the likelihood of an individual’s inclusion or exclusion from the development process. Within this framework, human exclusion is therefore considered the result of social, economic, political, institutional and cultural barriers that limit the individual’s capacity to benefit from and contribute to the development process.

Human exclusion can manifest at different stages of a person’s life. Infants might receive adequate nutrition during the early stages of life but later face discrimination in school or at the workplace. Often, however, exclusion can have long-term consequences, perpetuating a condition of being excluded over an entire lifetime. An example is the consequences of a child malnutrition on his/her educational achievements and opportunities later in life. This is why it is fundamental to address the factors that affect exclusion from the very first years in life.

Impact of exclusion on women and men

In each phase of life, women and girls are vulnerable to a different extent and in different ways than men and boys. The reason is that women and men have different roles in society, different access to and control over resources, and different concerns that can affect their likelihood of being included or excluded from mainstream development.

These differences might be gender-based or result from cultural biases and social factors. Studies show that women and girls:

• tend to provide unpaid care work

• are generally paid lower wages

• experience more than boys the consequences of a truncated education

• are more likely to enter into unskilled informal labor

• are more often subjected to exploitation, violence, or early marriage.

These differences might affect their future development and ability to participate in social, economic, and decision-making processes.

The effects can vary across life stages. In developing countries, girls who reach adulthood have a life expectancy that approaches that of women in developed countries, a gap that is likely to narrow as mortality rates decline among young age groups. On the other hand, child malnutrition is typically higher among boys than girls in most developing countries.

Early marriage and other traditional practices can determine girls’ educational achievements, lowering their future life opportunities and aspirations. Policies that do not adequately address these differential outcomes—whether based on contextual factors or intrinsic to gender—tend to perpetuate gender inequalities and exclusion.

Exclusion in urban and rural areas

Exclusion is also influenced by where a person is born and lives. Rural residents are more likely to lack the minimum social and economic infrastructure—including basic social services—that allows them to develop to their full potential. Globally, 75% of those living in extreme poverty in 2002 resided in rural areas, although rural residents made up only 52% of the world population.

African cities also face challenges such as urban congestion, environmental and health hazards, poor infrastructure, social fragmentation, limited access to land, and increased competition that bars unskilled workers from economic and social opportunities.